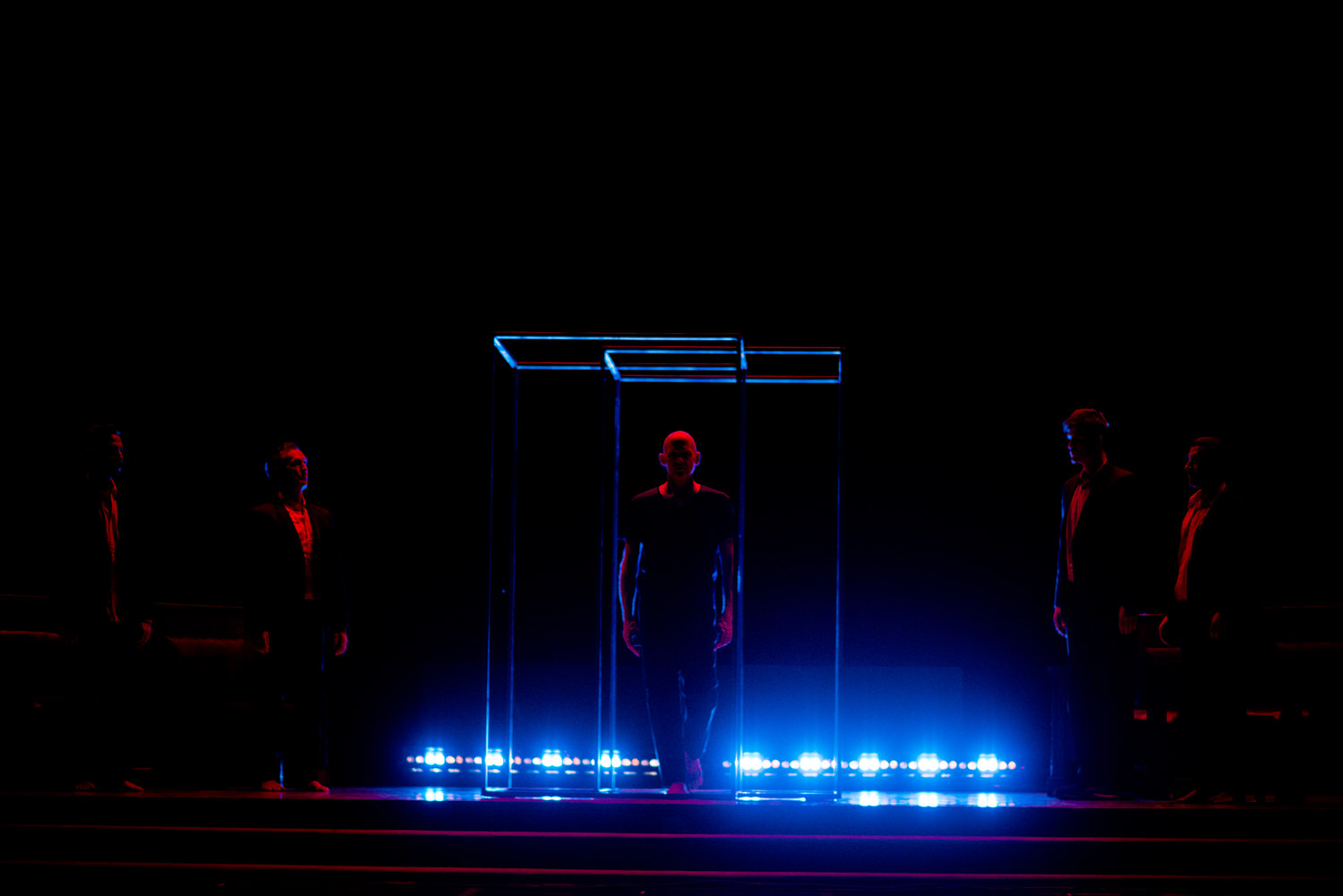

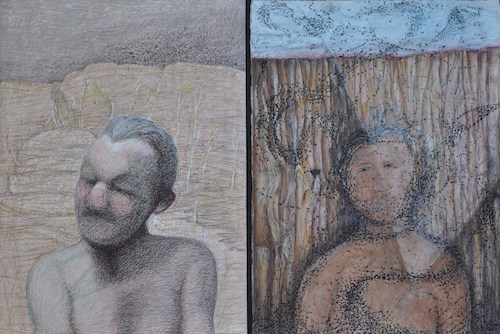

Brian Wakelin (Photo by Soloman Chiniquay)

As part of NOW-ID's ongoing interview series Ne Plus Ultra that shares the stories of artists and designers creating extraordinary, inspiring and impactful work, we are delighted and honoured to share the thoughts of our friend Brian Wakelin. Brian is an architect and co-founder of design firm Public Architecture, based in Vancouver, British Columbia.

A thought leader and natural collaborator, Brian has worked in the architectural field for nearly thirty years and holds a Master of Architecture degree from the University of British Columbia. His design work is widely recognized and has received six AIBC awards and three awards from SCUP/AIA. Brian has presented his work at several national conferences and his writings have appeared in Design Quarterly, Academic Matters Journal, and SAB Magazine. He has a track record for achieving consensus with diverse and complex educational, First Nation and other government clients.

Tell us a little bit about your background. When, where and why did your interest in architecture emerge?

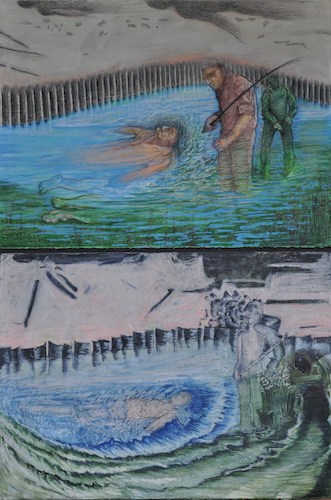

Full disclosure: my dad was an architect. He didn’t practice during my lifetime; he’d retrained as a planner by the time I was born. But he was one of those people who could draw anything. We took a long train ride when I was a kid. To amuse each other we passed doodles back and forth challenging the other to transform the scribble into pictures of things like elephants and snakes. When we went through a long tunnel I scribbled and scribbled on that note pad determined to stump him. When we reached day light with a few strokes of his pilot marker he turned the scribbled black mess into a thunder cloud over someone fishing in a boat. I just loved how he conjured something from a mess. Eternally optimistic and a student of cities, he was a great mentor and set me on my path.

How long did it take for you to build your company Public Architecture to become a sustainable business and did you know quite early on that you wanted to start your own company and if so, why?

I didn’t set out from school planning to start a firm. Not that it was daunting. There was just so much energy spent with projects that the layer of firm ownership just wasn’t on my mind. I’d been working for a decade for an architect who was a notorious critic. He could be tough, but the process forced me to become sure of my work and reasoning.

I was leading the design for a large research laboratory. I had a pin up with Peter to review the material I was going to present at a client meeting. I laid out a clear design development presentation. I covered every inch of the meeting room with models, diagrams and orthographics. My team was excellent. He came into the meeting room, one on one, ready for battle. He scrutinized the model and everything on the wall, asking me questions. Thinking the steps through. He left the room, with a “looks good”. With no battles, no revisions, and no sleepless nights, I decided then and there that it was time to go.

I left the firm without any prospects. I took two months off to be with my young family and recharge. After that I joined with partners John Wall and Susan Mavor and started small working from the kitchen table. We sought clients as much as projects. Growth was slow and organic, one project at a time. By specializing in public work, we were an outlier, and our work resonated with key universities and municipal governments. By our second year we had a growing team and paid rent like grownups. We spent seven or eight years in a narrow downtown office sitting at one table – a 50’ long version of the dining table we started on. When we relocated into a more comfortable setting, we were able to loosen the belt so to speak and expand our leadership group. Its hard to describe the satisfaction seeing work on the walls that I didn’t directly have a hand in. The founders set the table, but a new generation is now serving up some gratifying dishes.

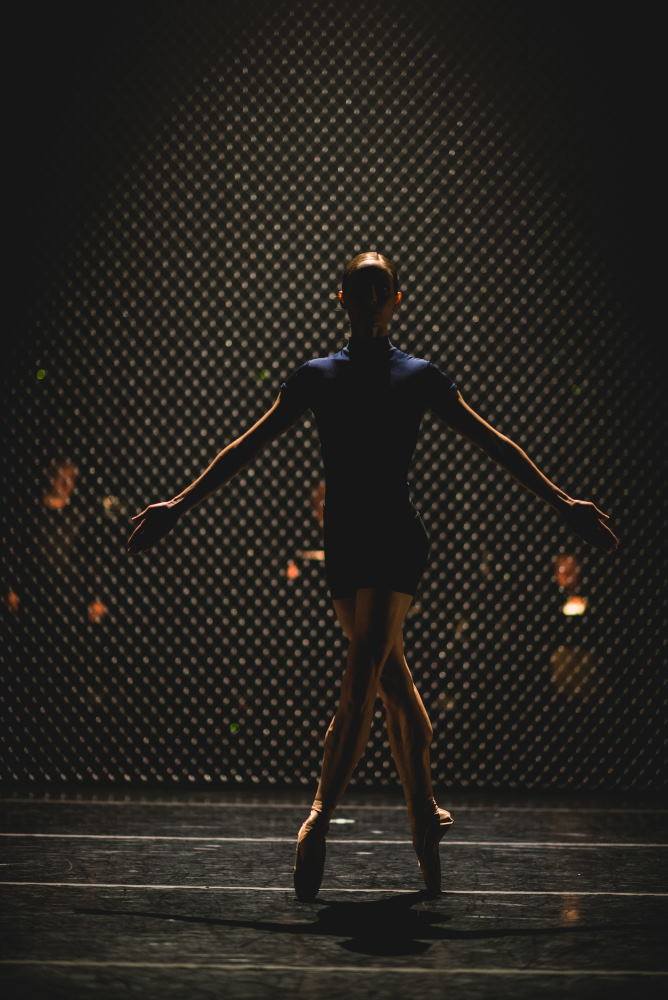

Brian together with John Wall and Susan Mavor (Photo by Scott Massey)

What projects helped define your company and why and can you talk a little bit about the philosophy and values that Public was founded on?

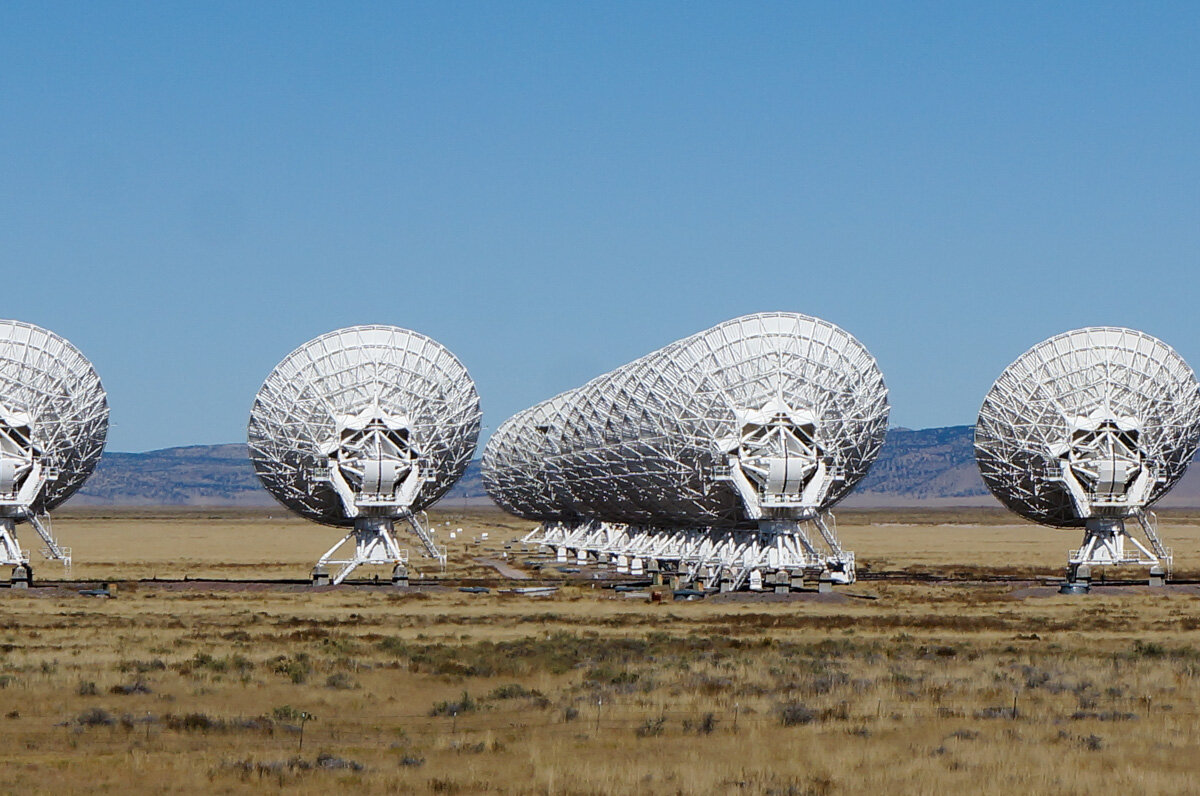

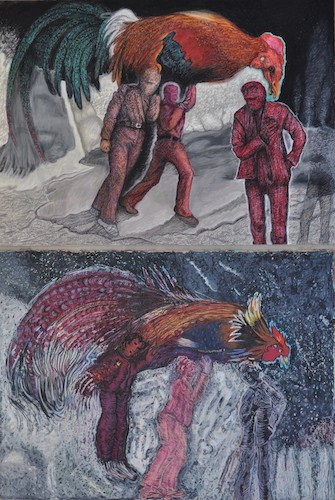

Buchanan Courtyards would be a standout starting project for us. It was an interdisciplinary and collaborative early work. Our client, UBC had a space that was underperforming. It was modern, established in the early sixties and beautiful. But a single use space only which was not widely appreciated on campus. A new campus architect had just initiated a public realm renewal program, and this was the inaugural project. PFS led the landscape effort adroitly, and PUBLIC brought a lens to urban design elements and an outdoor performance pavilion.

Buchanan Courtyards (Photos by Nic Lehoux)

Our impact with this project came from finding harmony among disciplines--wayfinding, artwork, landscape and architecture. We started PUBLIC with an ambition to be open to collaborators from different branches of design. This project was the first to manifest that. Making a place without a building was also new to many of us and exciting. We were also struck by the variety of processes of different disciplines. Communication designers for instance, work very quickly. Landscape architects work more slowly but of course are dealing with the uncertainty of organic things and processes. Architecture is somewhere in between. This experience loosened our process in many ways, allowing us to consider architecture that could be graphic. Later, the Stewart Blusson Quantum Matter Institute would express its hermetic workings to the same campus with an expressive masonry skin. Adler University's Vancouver campus took this a step further in a vertical campus of drywall surfaces that supported vibrant graphics. The campus, veiled behind five stories of curtainwall, connects to the city and makes it a backdrop to student experience.

Vienna House, Adler University, UBC Quantum Matter Institute (Photos by Martin Tessler)

What is the most challenging aspect of running an architectural firm in Vancouver and what do you appreciate the most about working in Vancouver?

The rich long history of this place. From the philosophies and worldviews of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm , Skwxwú7mesh, and Səl̓ílwətaʔ Nations, which have challenged and influenced my thinking and our practice. I am grateful for the teaching of this place and hope to facilitate the work of reconciliation.

What type of projects do you prefer to work on and why?

The programs vary, but the commonality in our strongest projects is large and diverse clients. Achieving and maintaining momentum and consensus in dynamic groups is more art than science and is something we’ve worked hard on over the years. These tensions result in better work.

What or who inspires you in your creative process?

My inner dialogue echos the voices of my late father and my children. Questions like, will this make a better city, will it make people’s lives better, am I doing this in a way that is sustainable, is it rigorous? I'm blessed to be supported by a great team. We’ve added another partner Robert Drew and the next level of leadership, Shane O’Neill, Martina Caniglia and Jamie Harte are infusing the work with energy. Additionally, we have more than a dozen countries of origins represented at the firm, which brings vital new perspectives. We all benefit from fresh voices.

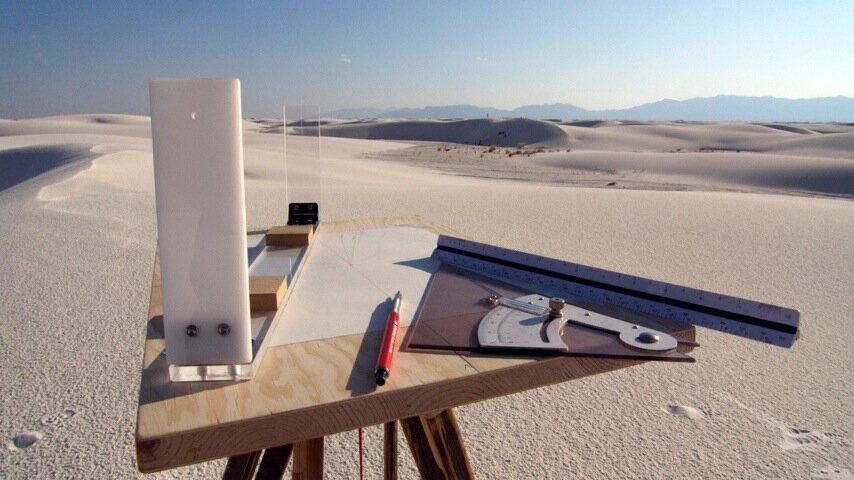

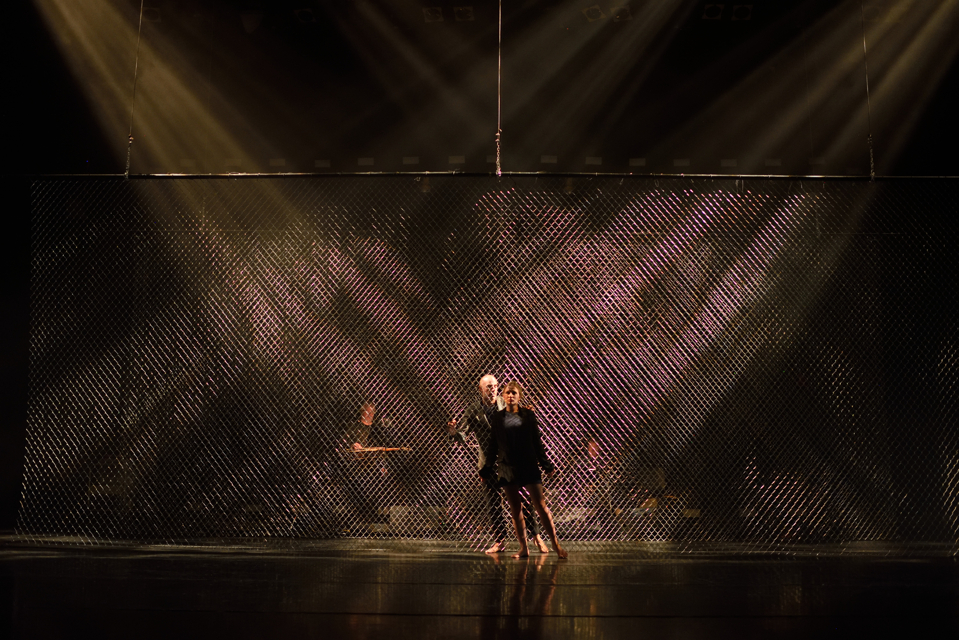

Photo on the left by Soloman Chiniquay

Are there cities that you have traveled to that have inspired your work?

We were Rome Prize winners which allowed us to spend time in Copenhagen, Rotterdam and Tokyo. Once you’ve lived in those cities they become embedded in you. That time opened our process. We experienced a gamut of buildings, some well-known, most not, that organized familiar programs in unfamiliar ways. Post Prix de Rome we had fewer preconceptions, we shared more process with clients, allowing them to look under the hood so to speak at PUBLIC. Previously we had been guarded, developing designs with our clients, even with our staff, with carefully curated iterations only. A more open process, where all options are on the table, builds trust and consensus quickly and pushes us out of our comfort zone, which is a positive shift.

Is Vancouver, in your mind, a city that is ambitious enough design wise?

Whose Vancouver? The Vancouver that concentrates global capital in downtown peninsula towers or in gracious and expansive homes is regarded by the media as ambitious. Unfortunately, an overwhelming amount of housing supply fits neither of these categories and is ignored by the media. I have sat on several civic design review panels and witnessed a depressing number of proposals with little consideration for families, ill-suited to climate change, and poor candidates for social resiliency. In addition, many Vancouverites, ironically including the architectural interns that produce the work noted above, live with housing insecurity due to a lack of affordable housing. Not to mention there is a disproportionate number of people in our city with no housing at all. In answer to your question, sadly, Vancouver is not ambitious.

What are your ambitions for Public Architecture moving forward?

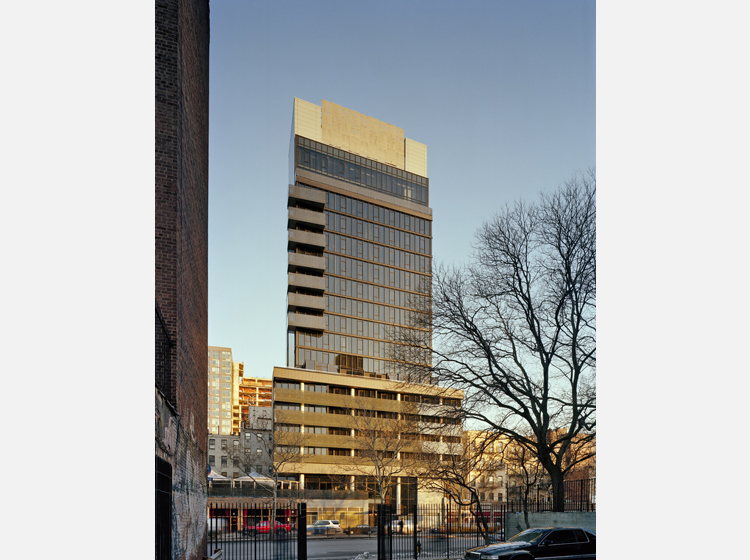

Our work has shifted over the last few years to creating housing and community services for families. Vienna House is a good example. We recently contributed to changes in the BC Building Code to permit single stair multifamily dwellings. Single stair access will allow apartments similar to those found in Copenhagen for example. This small code amendment opens the door to housing that is more economical to construct and offers more possibilities for dwellings that better serve families.

Vienna House (Left two images by Andrew Latreille)

Where do you see yourself in 25 years?

I tease my peers about this question regularly. It takes a long time to mature as an architect, and I believe the least you can do is contribute while you’re at your peak. I’m not sure if I’ll go as long as Niemeyer, who seemed to be working into his hundreds, but Lewerentz and Michelucci are heroes with significant late career works. Touch wood - I’ll have a choice about what I want to do. Stay tuned!